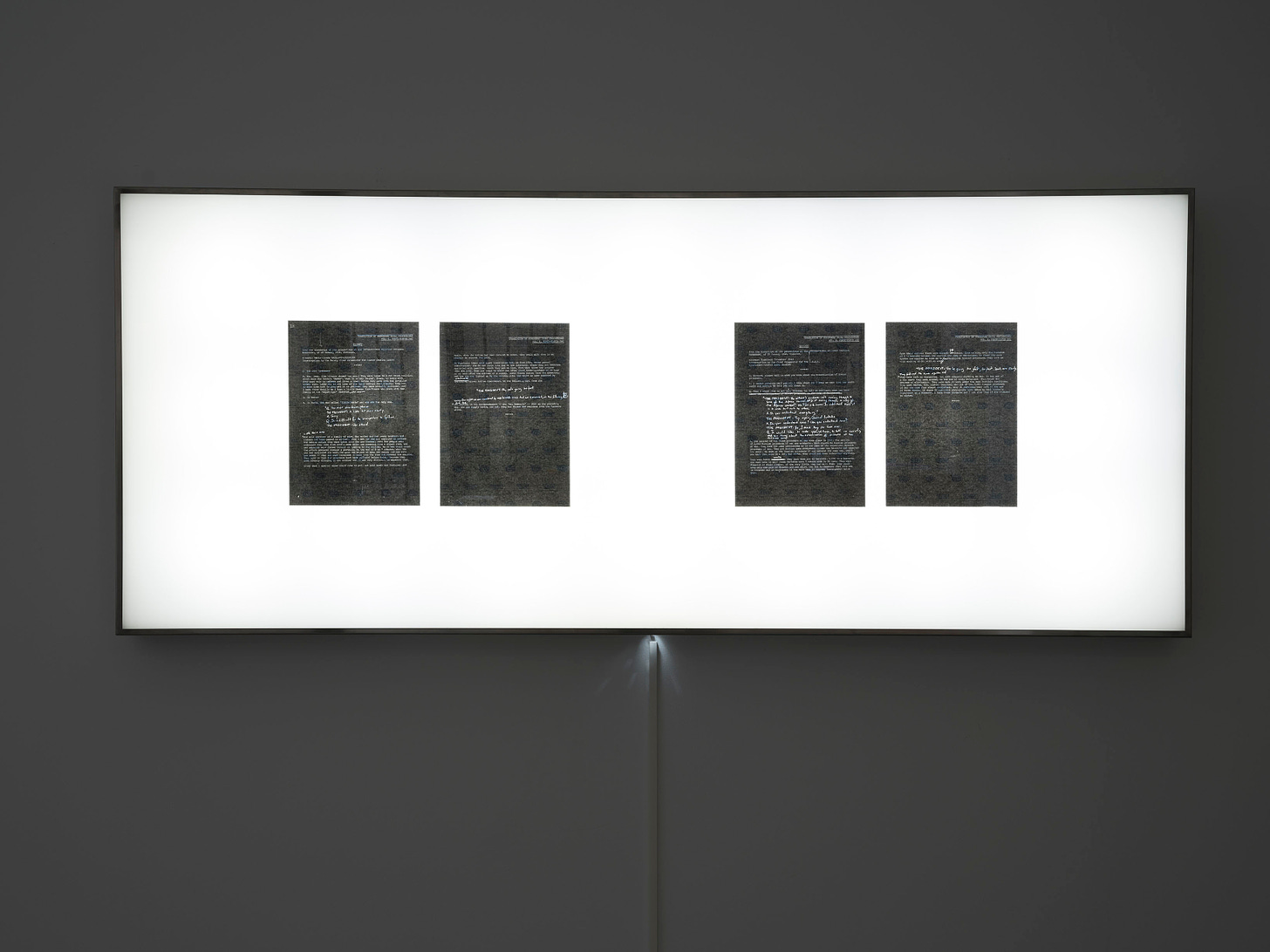

Cold light hangs on a wall on the ground floor. Three light boxes display ten carbon paper transcripts (Errata, 2022). Typed and inscribed in white, the black pages are witness testimonies from the Nuremberg trials (1945-1946). A vertical screen and a bench occupy a corner of the gallery. Concentrated reading drowns out the sound of the video. Left to right, illuminated sheets pass towards the sound. One, ‘TRANSLATION OF NUREMBERG TRIAL PROCEEDINGS VOL. 8, SIXTY-EIGHTH DAY’, is dated 26 February 1946. The witness is a Soviet civilian, Jacob Grigoriev. The Assistant Prosecutor for the Soviet Union, Chief Counsellor Lev Smirnov, performs the interrogation.

He asked Grigoriev, “In which village did you live before the war?”

He answered, “In the village of Kusnezovo, Porkhov region, district of Pskov.”

Smirnov repeated the question. Grigoriev answered once again.

“In the village of Kusnezovo.”

There is no apparent reason for the echo. As far as the transcript shows, the question was answered and understood. Below, Smirnov asks if the village still exists. It does not. Beneath, between lines in the typed transcript, a white-inked passage of questioning begins from the President, British judge Geoffrey Lawrence. Interrupting the trial, he instructs Grigoriev.

“You must answer slowly, and after pausing because the question has got to go through the interpreters and your answer has got to go through the interpreters. Do you understand?”

The witness said he does. Smirnov asked again if the village still exists; and as before, he answered that it does not. Jacob Grigoriev described the day in October 1943 when German soldiers raided his village, shot and murdered his neighbours and ordered him and his son to follow them.

Downstairs and around the staircase, seven brushed-metal podiums encircle the room (The Witness-Machine Complex, 2020-2021). The podium levels with the chest of a standing witness. A silver, fine-mesh grill amplifies testimonial statements on one side. On the rear, a projector shelters within. Lit up on the walls are the projected words. Atop each podium’s surface erupts the spheres of a yellow and red bulb. In Nuremberg, when Jacob Grigoriev answered his question, too quick for the interpreters to transcribe, a yellow bulb in front of him flashed. If an interpreter required Jacob Grigoriev to speak again, a red bulb in front of him would flare. One to slow the witness and the other to make him stop. No documentation of the lights’ use is found in the written transcripts or the audio recordings of the Nuremberg trials. The bulbs only appear in the film archives. In the official record, the transcripts are perfect. Errors and administrative duties are removed. Only in Hamdan’s Errata (2021) are the hand-scrawled interruptions and mistakes made visible. The horrific witness testimonies and the mundane functions of the court instruments create a sound of their own. The heterogeneous constituents realise a new site of empathy in the well-documented history.

Simultaneous interpretation is the exceptional human ability to translate language in real-time. Nuremberg interpreters worked every word spoken to the court into four languages. Twelve interpreters in the court, three to a booth. One English, French, German and Russian. In the German booth, one interpreter processed the English speakers, another the Russian and the last the French. Cables snaked from beneath and inside each glass-partitioned station. The three interpreters shared a microphone and each worker wore a headset. Each wired to the witness stand. The wires linked everyone in the room to one of their microphones. In each booth, a monitor worked to control the yellow and red lights. On either side of their headphones, two language channels sounded. A sonic observer between the interpreters and witnesses. With eight to ten seconds to interpret each statement, the challenging requirement demanded of the twelve workers was to learn to talk and listen together. Upstairs, Lawrence Abu Hamdan’s video, A Thousand White Plastic Chairs (2021), continues to play. The screen remains blank. Black. Only when Hamdan’s voice fastens does the yellow light illuminate the frame. He is sitting at a desk. His voice recounts the select experiences of the many interpreters who worked in the court. After serving in the United States Army interrogating German prisoners of war, Henry A. Lea learnt to interpret speech with the sweep hand of a clock. Lea’s consciousness hadn’t the time to actualise the statements into meaning. The mechanics of the task dampened the accounts delivered by the witnesses and defendants. An administrative experience presents a protective vehicle for navigating atrocities. The horror is assuaged by monotony.

Another transcript excerpt, ‘TRANSLATION OF NUREMBERG TRIAL PROCEEDINGS VOL. 6, FORTY-FIFTH DAY’, dated 29 January 1946, is mounted on the second lightbox. The witness, Spanish photographer Francisco ‘Francois’ Boix, is interrogated by Chief Prosecutor for the Soviet Union, Lieutenant-General Roman Rudenko.

“Witness, please tell us what you know about the extermination of Soviet prisoners.”

He cannot, he countered, “I know so much that one month would not suffice to tell you all about it.”

Another interruption in the text follows. A handwritten scrawl creates a break in the machine-laid type. The President had notified the court that the defence counsel was not receiving the witness’s testimony. He said, “No? It is to some. I understand that it is to some but not to others.” The technology for simultaneous interpretation had failed. The witness asked if he was understood and the President instructed the Lieutenant-General to continue. Rudenko narrowed the range of his question:

“I would like to ask you, Witness, to tell us concisely what you know about the extermination of prisoners at the Mauthausen camp.”

Francisco ‘Francois’ Boix delivered his testimony. He spoke of the first 2,000 Russian prisoners of war to arrive in 1941. “They were human wrecks.” Overcrowded in barracks, their clothes were stripped of them. The witness described how the Nazis left each prisoner with one pair of underwear and a shirt. “One has to remember that this was in November and in Mauthausen it was more than 10 degrees (centigrade) below zero.” Twenty-four died walking four kilometres from the station to the camp.

“You’re going too fast, too fast. Speak more slowly.” The President interjected. The interpreters were unable to keep pace. The reader is pulled from the Mauthausen camp and into the courtroom.

Boix continued once more, he told the court of the scarcity of food. “Then began the process of elimination.” He recalls, “they were beaten, hit, kicked, insulted; and out of the 7,000 Russian prisoners of war who came from almost everywhere, only 30 survivors were left at the end of three months.”

Hamdan’s Errata (2021) unites bureaucracy and atrocity, the technical failures and brutal ethical lapses. The new history built between the lines of typed text disrupts a settled understanding of the proceedings. Retrieved from audio recordings of the Trials and rendered in handwritten ink, the unperfected documents front normalcy in the patriotic imagining of national histories and abuses.

Does the interpreter occupy the courtroom in the same capacity as the judge? Or the witness? Is an understanding of the Trials ever settled? In Lord Justice Geoffrey Lawrence’s ears, he heard the English translation over the headset. In the interpreters’ ears, it was the witness’s voice; their bodies became something automated and porous. The stenographer is the interpreters’ psycho-mechanical companion. Hamdan’s voice, in A Thousand White Plastic Chairs (2021), describes an encounter with a court stenographer in London. When focused on the transcription of fast-fading words, the worker’s eyes lock on a piece of cornice, a floral motif or a feature and free the space between their fingers and thoughts. Hamdan calls it an “acoustic forcefield”. The workers listen and speak without absorbing meaning. Many of the Nuremberg interpreters would eventually hear the court proceedings. Where, then, information processing reoccurred. Anew, the (recorded) testimonies took on another form. The voice of the witness can no longer be neutral but, rather, corrosive to the mind. Hamdan’s altered transcripts challenge the apparent benignity of bureaucratic documentation. He embeds new meaning with an exposition of aesthetic mundanity. Stone-carved texts are broken with lines of white ink. Yellow and red lightbulbs illuminate horror in the banality of procedure. The shielding effect of dissociative comprehension creates a site of empathetic sound. A new glint of compassion appears through a sonic fracture into the past.

—Andy x

A Site of Empathetic Sound, Errata by Lawrence Abu Hamdan