Pulling Threads, Jamie Crewe's DEMONIC HALF-PERSON, a Diary Entry

Thoughts on Jamie Crewe's artist talk at Open School East

I wrote this on the train from Margate to London, after Jamie Crewe’s artist talk DEMONIC HALF-PERSON at Open School East co-facilitated by Emelia Kerr Beale.

21:19 — Leaving Canterbury West

I’m in a further-away part of the country cruising on a lightly motioning empty carriage writing to myself, waiting for the time to pass. I have it in this site of near-hell-like conditions; repetitions made pleasurable though oft-characterised as tempestuous or malignant—maybe just boring; are train journey’s sinful self-pleasure? My vision is doubling from the wine, from my amblyopia that drives the right eye out the blackened window into only a reflection of the wayward orb itself. I draw it back in with a technique learned as a child, with a lollypop stick printed with a bird illustration on one end, narrowing in size on approach to my nose.

21:38 — Leaving Ashford International

Jamie talked about a desire for obscurement, depth and withholding, but then contrarily, one for apparentness and access. Emelia had organised the event, as forced to by the requirements of their course at Open School East where they’re called an Associate in a quasi-bizarre chamber-like fashion, donned up in a suit to wield legal jargon, holding on tight to an iPad at their chest. The preamble, the talk itself, the Q&A were adhered to in a routine familiar yet welcoming, maybe only for my closeness to a friend. Regardless, Jamie worked through her past exhibitions, past art, past music, pulling their threads out and up to reveal the techniques she often finds in them herself, naming them when discovered, such as that of this evening’s title, Demonic Half-Person.

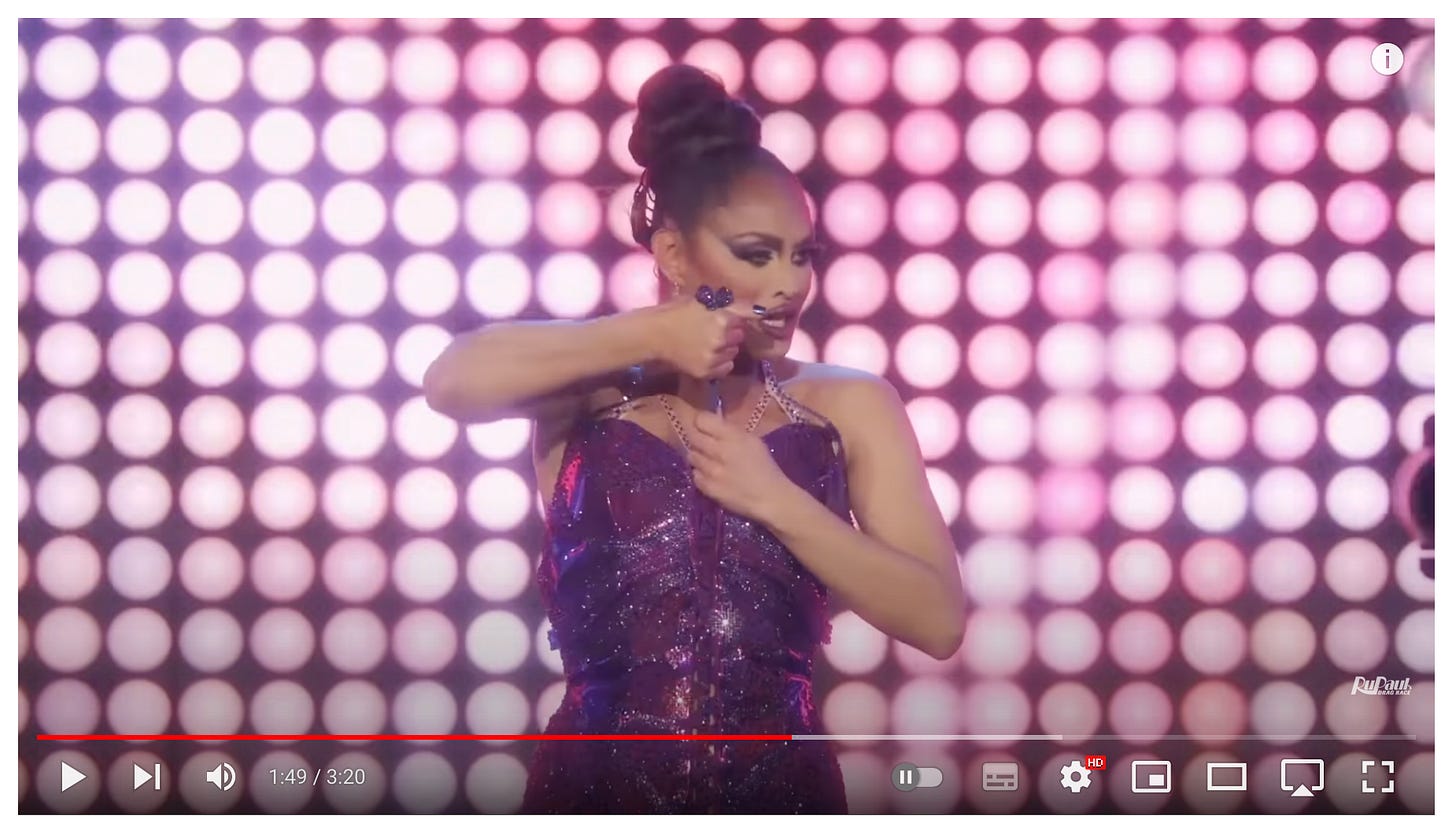

Jamie made a throwaway comment, that the threads she pulls were like Sasha Colby’s dress during the final lip sync to end her winning (spoilers) season of Rupaul’s Drag Race, where a cord is removed from interwoven fabric fed up the centre front of her garment. The two sides split away to reveal another outfit beneath. Thinking of pulled threads, I thought of an urban legend. I say it’s an urban legend because I’ve heard the story too many times, each time beginning, ‘I have a friend of a friend who recently got a nipple piercing.’ The story goes, and I’ll steamroll it here for brevity, that upon piercing their nipple a friend of a friend spots a stray hair sprouting from the newly poked flesh, a little wiry one; and bothered by it, the friend of a friend gives it a tug—though not to reveal Sasha Colby’s body, or an aspect of Jamie’s practice—but to simultaneously vomit, shit and piss themselves. For upon inspection, the hair was not cutaneous but in fact made of an exposed nerve ending. Revelatory nonetheless, in this urban fiction, who knew one had such a kill switch?

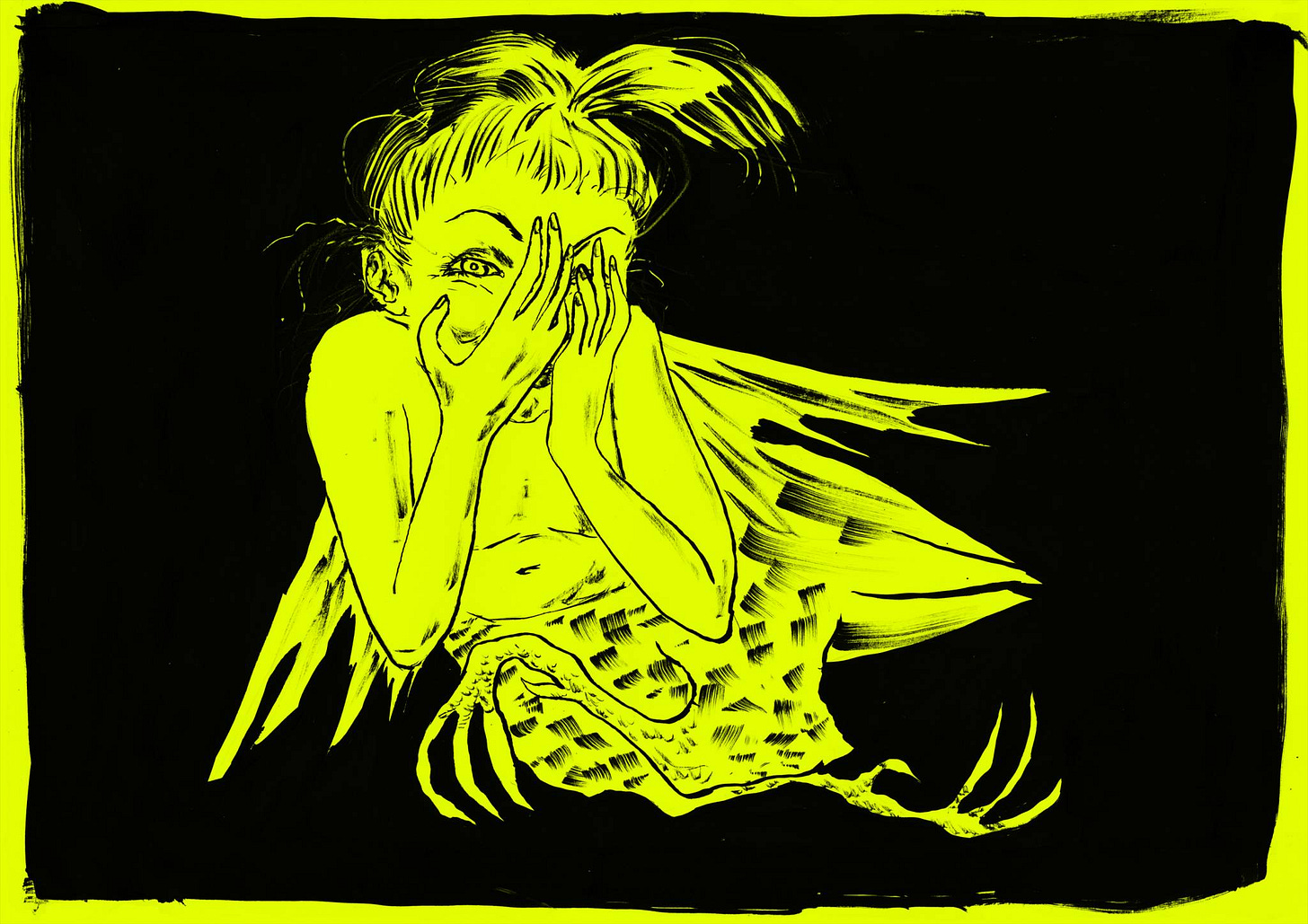

I like the idea of pulling on your own threads, walking yourself outwards and back in again, in a relationship between obscurity and otherwise. Listening to Jamie talk, the works in her practice are so rich with meanings, at times both evidently and otherwise. The hinge point not being solely on pure image alone; though those assemblages can enforce trancelike or jarring responses in the likes of False Wife (an amazing popper’s training video from 2022, commissioned by The University of Edinburgh Art Collection and Dr Chloë Kennedy); but too does the work’s narrative construction, response to site and context give access via burrowing points found within reference. Jamie said she thinks about parasites, being afraid of them, but nevertheless enjoying the idea of entering material that way; parasitically enveloped in meanings in order to liberate some of her own, permitting an audience in through those same white scabies scars.

21:59 — Arriving Ebbsfleet International

There is a friction in the use of historical material, such as the Victorian and Early Modern works of fiction often at the genesis of Jamie’s works, often at their centre are queer protagonists and antagonists. Some of her works resolve in adaptation, others as collusions or admirations. One of the most famous reference points, particularly among lesbians, Radclyffe Hall’s The Well of Loneliness sees itself in one of Jamie’s paintings, and in a remark during the talk about conflict embedded within queer spaces; between these at-odds colluders held beneath the same political banner. When the book’s protagonist is welcomed by an another ‘invert’, one she wishes not to be affiliated with, with the greeting, ma soeur; I think of trite anguish.

A space for sticky problems made roomy, not only in the work itself perhaps but in how it is discussed—a mode I have come to resent, this argumentative, text-based mode of art reading—which I might now reconsider and appreciate.

22:11 — Leaving Stratford International

22:20 — Arriving London St Pancras International

In the deft delivery of material—reference, artwork, story—the channels to entry become visible to me, whilst simultaneously having vomited, shit and pissed myself.

—Andy x

Note: That last line is such a weird way of saying ‘I was inspired’, ‘I will look at art a little differently’, or ‘wow, so good’.